Declassified files hint at CIA complicity in Walter Rodney’s murder

On June 13th 1980, renowned Guyanese political activist Dr. Walter Rodney was assassinated via car bomb. It would not be until almost 40-years later that an official inquiry concluded his slaying “could only” have been greenlit by the small Caribbean country’s then-Prime Minister Forbes Burnham.

Those findings were recently accepted by Guyana’s parliament – to mark the occasion, the US National Security Archive has published a number of documents related to the event, released to the organization under Freedom of Information laws.

The trove includes the inquiry report - inexplicably not made public - which spells out in forensic and often shocking detail how Rodney was murdered, and the numerous high-ranking governmental actors that colluded to ensure his killer, Guyana Defence Force operative Gregory Smith, got away scott-free.

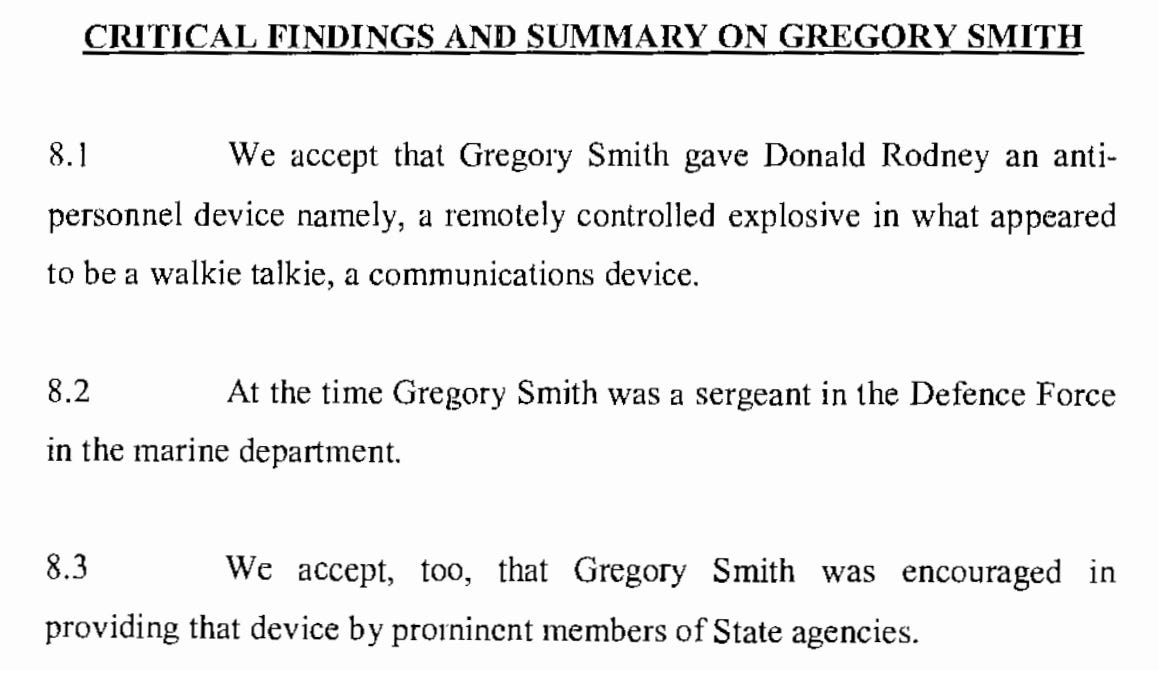

On the night of June 13th 1980, Smith – encouraged by “prominent members of state agencies” – provided Rodney and his brother Donald with a walkie-talkie that secretly contained a “remotely controlled explosive.” The pair had intended to use it to maintain “relatively easy contact” with fellow members of Working People’s Alliance (WPA), the political party Rodney founded in 1974, which sought to “[replace] ethnic politics with revolutionary organisations based on class solidarity.”

Within hours of the resultant explosion, which killed Walter and severely injured Donald, Smith was flown via military aircraft to the northern village of Kwakwani, and provided with a forged passport in the name of Cyril Milton Johnson, courtesy of the Guyanese passport office and police force.

Then, by way of “state assistance”, he was spirited away to French Guiana, a choice of destination “no doubt informed” by the country’s opposition to the death penalty – “it would have been difficult, virtually impossible” to secure his extradition as a result. Smith eluded justice there until his death in 2002.

Burnham is furthermore revealed to have attended a meeting with senior officials within Guyana’s Special Branch, to be briefed on the plot, three days before it was carried out. That the Prime Minister had a keen interest in Rodney’s demise is unsurprising – a Marxist, Pan-Africanist and prominent figure in the region’s burgeoning Black Power movement, his WPA had bridged divides between Guyana’s East Indian and African populations, and was the most effective and credible opposition to the ruling People's National Congress.

These viewpoints and activities would inevitably also place Rodney in the crosshairs of the US Central Intelligence Agency, which helped install Burnham in power in 1964, in a lesser-known Cold War-era coup. The National Security Archive tranche can only raise significant questions about Langley’s foreknowledge of, if not complicity in, his cold-blooded assassination.

Once CIA, Always CIA

Take for example records of a December 1979 meeting between Rodney and the US embassy in Guyana’s political officer, Lee Adkins. The radical had specifically requested a “discreet” rendezvous, in order to allay American fears should the WPA take power in future.

The file notes that WPA representatives had been “making a special effort” to provide the diplomatic mission with copies of its “pamphlets and statements,” Rodney stressing that the party’s leaders didn’t consider Washington “the enemy,” any government they formed “would pose no threat to US interests,” and unavoidable differences over the role of Western corporations in Guyana wouldn’t mean a WPA administration viewed the US government “in an unfriendly light or in any way pose a threat to [its] national security.”

He went on to declare that the WPA had not received – and would never seek – assistance of any kind from Cuba, or “anyone who would seek to play an important role in shaping their future government.” Having previously taught in the US and “enjoyed his experiences immensely,” Rodney believed its “democratic atmosphere” was to be “admired and emulated,” even forecasting that the country “may turn out to be the most successful of all socialist states.” This statement reportedly produced “friendly differences” between the pair.

Still, Rodney suggested that repressive government measures targeting his movement could lead Guyana to “deteriorate into violence.” While he “abhorred terrorism,” the WPA “may be forced to resort to it,” with “some form of violent retaliation” potentially erupting “within the next year,” as young activists “tired of being pushed around by government thugs” may feel “the time had come to defend themselves” - “he, for one, intended to defend himself.”

Eerily, given what transpired just six months later, Adkins recorded that Rodney “gave the impression of a man who had a premonition of imminent death” – although, “he was not shrinking from that fate, but trying to put a few affairs in order before it came upon him.”

“Rodney asked [that I] assist his wife and children in obtaining permanent resident status in the US in the event he was killed…he wanted to make sure that in his absence, [they] would not have to remain at the mercy of the Burnham government,” Adkins wrote. “He emphasized that he was not asking for assistance for himself because his fight was here in Guyana, and he intended to see it through…[I] explained that such a request was not easy due to strict immigration regulations.”

Little did Rodney know, but Adkins was in fact a CIA operative embedded within the US embassy. The pair’s candid chat was no doubt a billowing red flag for the Agency – after all, Burnham had already caused consternation by nationalizing the country’s Bauxite reserves, among the world’s largest at 350-million tons. Furthermore, in March that year Maurice Bishop’s radical leftist New Jewel Movement had seized power in Grenada.

The prospect of another openly Marxist government taking root in the region via force would’ve been absolute anathema to Langley, and Rodney’s disclosures could well have spurred its operatives to action stations.

Adkins’ secret role was exposed by the Final Report of the Independent Counsel for Iran/Contra Matters, which recorded how he funneled “lethal and non-lethal” aid to the Contras via CIA helicopters during the Reagan administration’s secret dirty war against the Sandinistas, in breach of the Congressional Boland amendment, prohibiting US authorities from providing military support “for the purpose of overthrowing the government of Nicaragua.” The helicopters were then used to ferry cocaine back to the US.

While not prosecuted for his involvement in this sinister connivance, Adkin’s Agency post was nonetheless apparently terminated – in 1991, he publicly lamented that he was a “sacrificial lamb…[thrown] overboard to placate Congress.”

Still, in the spirit of “once CIA, always CIA”, after a more than decade-long stint running his own private security firm – during which time he was implicated in the intimidation and murder of Colombian coal industry trade unionists – Adkins was officially re-recruited by the Agency in 2003, by his own account because the Agency “was gathering [its] best men to overthrow Saddam Hussein.”

‘Delta Serra’

The documents abundantly show that the CIA and State Department took a keen interest in the police investigation into Rodney’s death from the moment it was launched, which was led by Cecil ‘Skip’ Roberts, head of Guyana's Criminal Investigation Division. He told the Embassy that the incident “could have been an accident,” which was apparently considered “plausible” by US diplomatic staff, at least initially.

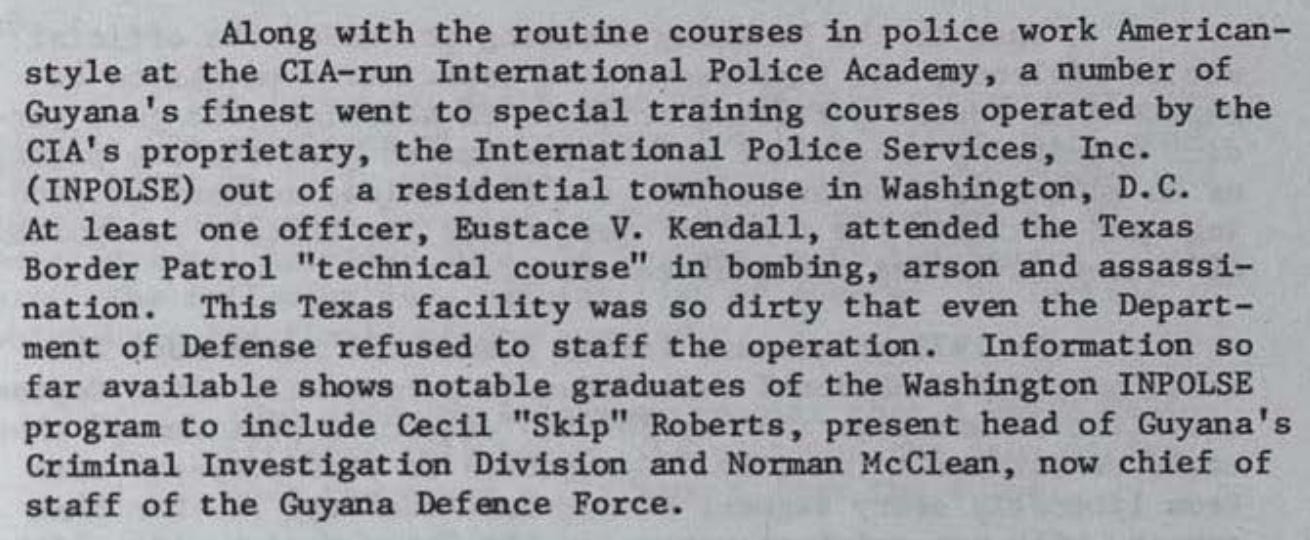

Strikingly, Covert Action Information Bulletin revealed at the time that Roberts was one of several high-ranking Guyanese law enforcement officials trained under the CIA’s International Police Services (INPOLSE) program, which tutored thousands of police officers the world over, and also supplied them with weapons and pacification equipment worth millions.

As Agency whistleblower Philip Agee attested in 1975, INPOLSE was used to conceal the training of individuals “you didn't want kicking around the Police Academy.” This included officials within Idi Amin’s monstrous Public Safety Unit, for instance.

At least one Guyanese officer tutored under its auspices, Eustace V. Kendall, attended a “technical course” in bombing, arson and assassination at a Texas Border Patrol facility secretly operated by the CIA. ‘Skip’ Roberts was also intimately involved in the probe of WPA activist Joshua Ramsammy’s attempted murder in October 1971. He was shot several times as he sat in his car outside Guyana’s National Cooperative Bank, miraculously surviving despite a bullet puncturing one of his lungs.

The assassins’ getaway vehicle was quickly traced to Hamilton Green, Guyana’s Minister of Labor and Health, and Burnham’s cousin – unsurprisingly, he was never arrested, let alone prosecuted.

Norman McClean, who one month to the day after Rodney’s murder was promoted to the head of the Guyanese Defence Force, was likewise an INPOLSE graduate. Covert Action records that he and Green visited Washington DC twice in the last week of May 1980, the former confiding “in several persons that the purpose of his visit was to acquire ‘electronic communications equipment’” – such as a walkie-talkie rigged with explosives, perhaps.

The official inquiry report finds that he as well as Roberts “had significant roles to play in the conspiracy to kill Dr. Walter Rodney and the subsequent attempt to conceal the circumstances surrounding his death.”

Despite the WPA having cracked the case within days – Donald fingered Gregory Smith as the individual responsible for providing the incendiary device – the US embassy clearly suspecting Guyanese government involvement, and a British bomb expert’s report specifying that Rodney’s killer could easily be identified via analysis of the walkie talkie’s frequency, the only person ever charged in the case was Donald himself.

Convicted of possessing explosives, he was sentenced to 18 months imprisonment. The Guyana Court of Appeal finally overturned this in April.