How Britain Invented Modern Torture

All my investigations are free to read, thanks to the generosity of my readers. Independent journalism nonetheless requires investment, so if you value this article or any others, please consider sharing, or even becoming a paid subscriber. Your support is always gratefully received, and will never be forgotten. To buy me a coffee or two, please click this link.

On January 2nd, Frank Kitson, a lifelong British Army officer, writer and military theorist died peacefully in his sleep, at the grand age of 97. It was an undeservedly dignified exit for an individual who directly and indirectly inflicted misery upon untold people, for much of his lifetime. Many will undoubtedly continue to suffer adverse consequences as a result of his teachings for decades to come.

Kitson was a pioneer in the field of counterinsurgency, defined as “the totality of actions aimed at defeating irregular forces.” His assorted views on the topic were informed by Britain’s experience of brutal, asymmetric wars against nationalist rebellions and attempted revolutions throughout the Global South, as its Empire rapidly disintegrated following World War II. In several cases, he was on the literal frontline of these bloody disputes.

Kitson wrote a series of books about counterinsurgency, which were hugely influential internationally. Most notoriously, his proposed strategies for “defeating irregular forces” were deployed throughout “the Troubles” - London’s secret dirty war against the Catholic population of Northern Ireland, and the Irish Republican Army (IRA). Ever since, these methods have been deployed over and again to devastating effect in theatres of war domestic and foreign, by multiple governments.

Even sympathetic mainstream obituaries of Kitson were forced to acknowledge this highly controversial legacy. The Times of London noted how in his final years, “he was still dogged by litigation” from his time leading Britain’s war on Catholics throughout the Troubles. “Threats to his personal security and that of his family continued to the end” as a result of his posting, the newspaper recorded.

Absent from these eulogies was any reference to a core, clandestine component of Kitson’s patented counterinsurgency credo - a very specific, uniquely British form of torture. Actively practised and exported abroad by London for decades, these techniques of maltreatment have been adopted by countless militaries, security and intelligence agencies, and police forces. Just as the primary casualties of battles against “irregular forces” are invariably innocent civilians, average citizens of the world have been the ultimate victims of this mephitic push.

‘Propaganda Cover’

In Autumn 1969, Kitson’s British Army superiors personally tasked him with an extremely sensitive mission. He was to enrol at Oxford University, and produce a thesis “to make the army ready to deal with subversion, insurrection and peace-keeping operations” over the next decade, if not beyond. The 42-year-old lieutenant colonel was an ideal candidate for the role.

Pyrrhic victory over the Nazis severely weakened London financially and militarily, prompting populations of her colonies and imperial holdings to rise up en-masse against their British oppressors. This produced bitter end-of-Empire wars on every continent. Kitson was a veteran of two - the 1952 - 1960 Mau Mau Rebellion in Kenya, and 1948 - 1960 Malayan Emergency. There, he witnessed first-hand the innovation of new, vicious ways of dealing with unconventional threats, in real-time.

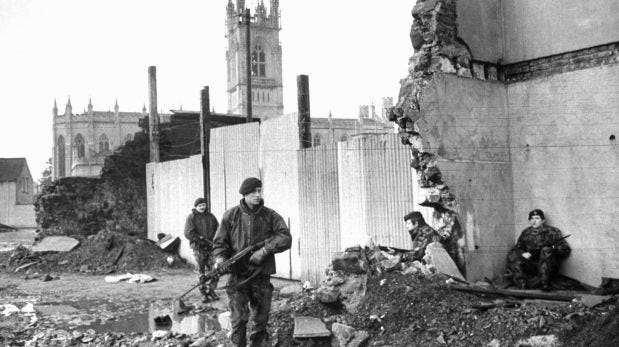

Kitson was dispatched to Oxford at a time London struggled desperately to contain another popular civilian rebellion. Escalating tensions between indigenous Catholics and Protestant colonisers in Northern Ireland resulted in the British Army’s formal deployment to the province in August 1969. Initially welcomed as protectors, the situation rapidly spun out of control. The “peacekeepers” became embroiled in endless, unwinnable street-to-street battles against IRA insurgency, and hostile Catholic civilians.

In September 1970, Kitson took command of the British Army’s 39th Brigade, responsible for keeping the peace in Belfast and much of the east of Northern Ireland. Serendipitously, his thesis was published as Low Intensity Operations: Subversion, Insurgency and Peacekeeping not long after. Received with some relief by soldiers, military chiefs, and government officials wrestling with how to deal with “the Troubles”, its contents provoked outcry in certain public quarters.

Of particular concern were passages in which Kitson argued that conducting counterinsurgency efforts “against those practising subversion” under typical civil, legal, and political conditions wouldn’t be feasible. Instead, he contended, standard freedoms, protections, and rights must be suspended before launching military operations against “irregular targets”. In such contexts, laws could not “remain impartial and [be administered] without any direction from the government”:

“Law should be used as just another weapon in the government’s arsenal…a propaganda cover for the disposal of unwanted members of the public. For this to happen efficiently, the activities of legal services have to be tied into the war effort in as discreet a way as possible.”

Elsewhere, Kitson likened counterinsurgency to catching a fish, with civilian populations of areas in which enemy groups operated as “the water in which the fish swims.” He argued that if a “fish” could not be caught via traditional means, “it may be necessary to do something to the water which will force the fish into a position where it can be caught. Conceivably it might be necessary to kill the fish by polluting the water.’’

‘Five Techniques’

In August 1971, Operation Demetrius commenced in Northern Ireland. British soldiers went home-to-home across the province, mass-arresting IRA suspects and their family members, frequently based on outdated or outright false intelligence, in service of “internment”. This policy was entirely in keeping with Kitson’s counterinsurgency pronouncements, and executed under his direct watch. It meant detention without trial for hundreds of “terrorism” suspects, over lengthy periods.

While jailed, internees were subjected to some or all of London’s “Five Techniques” of torture, to make them talk. These methods, in keeping with Kitson’s counterinsurgency philosophy, evolved over the course of Britain’s assorted end-of-Empire conflicts. Catholics were spared the absolute worst excesses of the horrors meted out to indigenous populations elsewhere. For example, while women were victims of internment, broken bottles, gun barrels, knives, snakes and hot eggs were not routinely thrust into their genitalia, as with female Mau Mau suspects in Kenya.

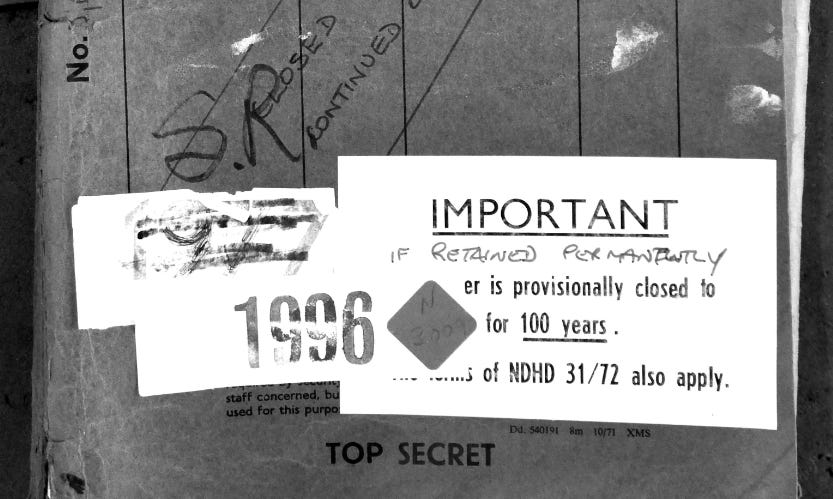

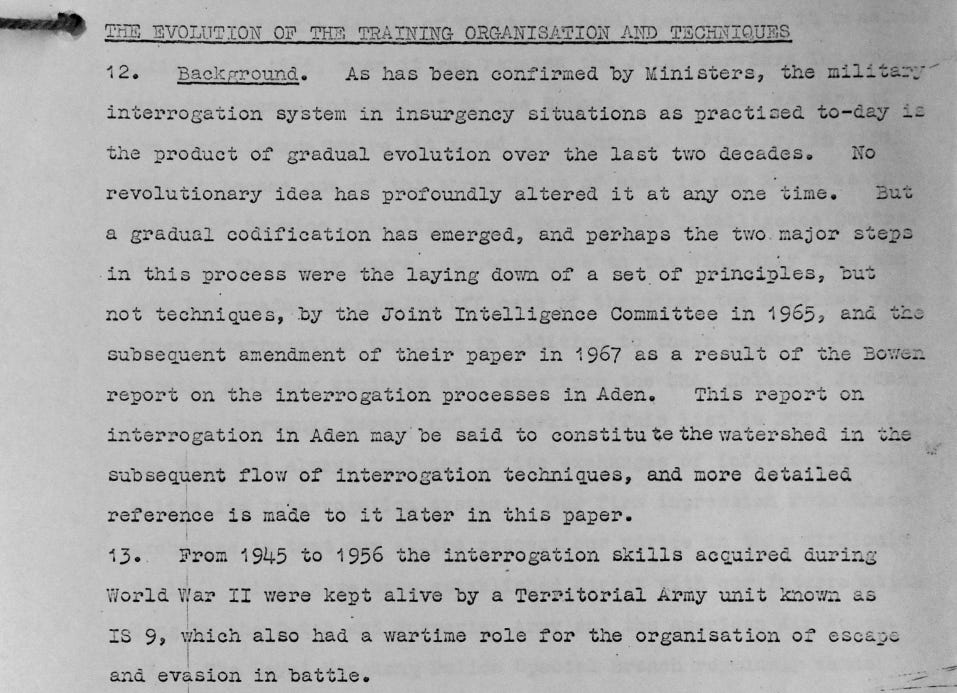

Still, what was done to detainees can only be considered barbarous in the absolute extreme. In November that year, a senior commandant within the British Army’s Intelligence Corps sketched an official history of the development of London’s military interrogation methods since World War II. Its contents were so sensitive, and shocking, senior government officials wished for the report to remain secret for a century. As it was, declassification came after just three decades.

In brief, Britain had devised a system of torture, combining prolonged stress positions, subjection to white noise, sensory deprivation, and cessation of food, drink, and sleep. The Five Techniques could be applied to anyone in almost any context, cost little or nothing to employ, and would not leave physical marks on victims. As such, public exposure, scandal or prosecution for human rights abuses and/or war crimes was extremely unlikely, if not impossible.

Physical pain and psychological devastation inflicted by the Five Techniques was nonetheless dependably gargantuan. In stress positions, detainees were stripped, then forced to wear buttonless boiler suits and hoods, before being forced to stand with their legs spread apart, leaning forward with their arms held high against a wall, supporting all their weight with their fingers alone. Simultaneously, relentless white noise was pumped into their cells. If a prisoner did not maintain the stress position, they were beaten into compliance.

‘Very Simple System’

The Intelligence Corps report notes these methods had been applied over the past three decades to prisoners of war, refugees, guerrilla fighters, and spies. Contained therein is a lengthy section documenting the deployment and refinement of the Five Techniques in numerous counterinsurgencies, while discussing their efficacy, and the results gained by usage. For example, the author cites how Mau Mau “terrorists” in Kenya “were persuaded under interrogation to switch their allegiance and subsequently guided British patrols against their erstwhile comrades.”

In British Cameroon 1960/1, “members of a subversive group from the neighbouring Cameroon Republic were arrested on British-controlled territory, which they were using as a base.” An Army team set up shop in a “converted hotel annex” to interrogate 20 “high grade subjects”, of which 15 “cooperated fully” as a result of torture:

“Information elicited included full details of rebel training camps in Morocco and other north-west African countries - even course syllabi.”

In June 1963, British Army interrogators flew to Swaziland, a protectorate of London, after 1,500 workers at a British-owned asbestos mine went on strike, demanding a basic wage of £1 a day. In a perverse irony, “it was thought that the labour problem [was] created by [a] subversive organisation,” rather than legitimate and reasonable grievances over grossly exploitative low wages paid by their colonial overlords.

After the Five Techniques were liberally applied to strikers - and, given their racial extraction, surely more gruesome methods too - “no subversive organisation was found” to be behind the strikes. This “negative result” was considered “valuable”, as “it quickly established that local grievances were the cause of unrest.” The effort was also “successful in clearing up the labour problems,” the report commended. But of course - when industrial action results in torture, workers quickly learn to stay in line.

Fast forward to March 1971, and a British Army interrogation centre was set up in a “disused camp” in Northern Ireland. The site “was not perfectly adaptable to the task, but was the best available,” the report records. The stage was thus set for Catholics to be subjected to the Five Techniques with total impunity. Savage tactics tested and honed against Africans, Asians, and Latin Americans were being brought “home” to British soil.

The report’s author well-understood the monstrousness that had been created. They noted the importance of training British soldiers to withstand comparable interrogation techniques, to know “what to expect at the hands of an unscrupulous enemy.” It is nonetheless likely British trainees were spared the indignity of being beaten, kicked in the genitals, and having their heads smashed into walls, as many Catholic internees suffered.

The result in every case was prolonged pain, physical and mental exhaustion, severe anxiety, depression, hallucinations, disorientation, and repeated loss of consciousness. No detainee ever fully recovered from their internment - long-term psychological trauma was universal. Yet, it appears only 14 prisoners were subjected to every single one of the Five Techniques. They became known as the “Hooded Men”, and in 1976, their case was considered by the European Commission of Human Rights. It ruled that the Techniques amounted to torture.

The case was then referred to the European Court of Human Rights, which astoundingly ruled two years later that while the Five Techniques were “inhuman and degrading”, and breached Article 3 of the European Convention on Human Rights, they did not amount to torture. In 2014, after it was revealed British government ministers had expressly greenlit use of the Five Techniques in Northern Ireland, Dublin asked the ECHR to review its decision. Four years later, the Court declined.

The declassified British Army Intelligence Corps report notes many foreign countries “show considerable interest” in the Five Techniques, with students from the US, Netherlands, Jordan, Belgium, Germany, Norway and Denmark regularly attending training sessions convened by London. “Our European allies look to the UK for advice…our very simple system is admired,” the report boasts. Which surely explains why the Five Techniques cannot be formally recognised as torture by the most influential and powerful human rights court in the world.

(“Law should be used as just another weapon in the government’s arsenal…a propaganda cover for the disposal of unwanted members of the public. For this to happen efficiently, the activities of legal services have to be tied into the war effort in as discreet a way as possible.”)-

I think it is clear that is the case more and more in the USA. The corrupt Establishment is engaged in an open "counter insurgency" against the American people.

Really enjoyed this article. In 1998 while preparing a BBC2 documentary on the Malayan Emergency (The Undeclared War) which featured Chin Peng the secretary-general of the Communist Party of Malaya (CPM) , other Malayan communists and assorted British military, intelligence and civil service personnel, I contacted Frank Kitson. I was told to write to his bank manager at Lloyds Bank in Torbay, Devon which I duly did. After a few weeks the bank manager replied saying General Kitson did not feel he had anything to contribute. Instead, I made do with General Sir Walter Walker who was living in Dorset attended by Gurkha servants. He made outlandish and lurid unsupported claims about the ‘communist terrorists’ (CTs) slitting open the stomachs of babies (shades of today’s allegations in Gaza). Walker had been part of an attempted coup d’etat in the mid-1970s that sought to overthrow the Wilson government and replace it with a junta led by Louis Mountbatten. Mountbatten declined, the plot fizzled out and Walter Walker wrote to me after our film was shown on the 50th anniversary of the Emergency declaration to say how much he regretted taking part. Chin Peng came to London for the broadcast – was interviewed by Neal Ascherson for the Observer and attended a premiere party at the now defunct Commonwealth Institute where he met Hugh Humphrey the British colonial civil servant who drafted the Emergency law – a document that became the blueprint for repeats in Kenya, Northern Ireland and elsewhere and is still in place, I believe, in Singapore and possibly Malaysia. Humphrey said to Chin Peng ‘you ran a very good Emergency’ and Chin Peng replied, ‘but you ran a better one’. It was an amazing meeting which I regret we did not photograph or film – partly out of respect for Chin Peng’s habitual suspicion. I remember we had to deal with the Foreign Office to get him a visa because in 1998 he was still on a list of barred terrorists. In fact, Kitson would have had a great deal to contribute to our film – but his spirit and MO were adequately represented by Walker and other military intelligence officers like Harvey Ryves.